- Topics

- /

- Design patterns

- /

- Idempotency - Challenges and Solutions Over HTTP

Idempotency - Challenges and Solutions Over HTTP

An idempotent operation is one that has the same effect whether it is performed once or many times. At Ably, we provide idempotent semantics for publishing messages via REST. This article shares what we learned about identifying and overcoming engineering challenges associated with providing idempotent guarantees over a globally-distributed messaging platform.

Idempotency and HTTP

HTTP is a widely adopted, straightforward protocol that allows clients to send requests to a server and receive a response. A lot of these operations are implicitly idempotent, i.e. by performing the same request multiple times, you are guaranteed to get the same result. The HTTP1.1 RFC Spec 2616 states:

"Methods can also have the property of “idempotence” in that (aside from error or expiration issues) the side-effects of N > 0 identical requests is the same as for a single request. The methods GET, HEAD, PUT and DELETE share this property. Also, the methods OPTIONS and TRACE should not have side effects, and so are inherently idempotent."

GET and HEAD operations are additionally defined as ‘safe’ which means they should have no side effects and thus should not have the significance of taking an action other than retrieval.

For developers, this is good news. We know that in a “correctly” behaving system, GET and HEAD operations never have side effects, and OPTIONS, PUT and DELETE operations are idempotent.

The table below summarises which HTTP methods are defined to be safe and idempotent according to the HTTP RFC Spec 2616, and, as developers, we expect we can trust HTTP servers to honor this:

| HTTP method | Idempotent | Safe |

|---|---|---|

| GET | Yes | Yes |

| HEAD | Yes | Yes |

| OPTIONS | Yes | No |

| PUT | Yes | No |

| DELETE | Yes | No |

| POST | No | No |

| PATCH | No | No |

The problem with POST

There are many operations that do have side effects – such as creating or uploading resources – which don’t fit the defined semantics of PUT, PATCH or DELETE. These operations, in the HTTP model, require the use of POST. The problem is that POST is not guaranteed to be idempotent.

In the world of distributed systems and services that provide contracts in terms of what onward processing happens for POST requests, this can be a significant problem. Consider, for example, a scenario where a client is using HTTP to publish a message containing transaction details into a pub/sub system which in turn broadcasts that message to subscribers. In this case, publishing the message multiple times will incorrectly result in the transaction being processed multiple times.

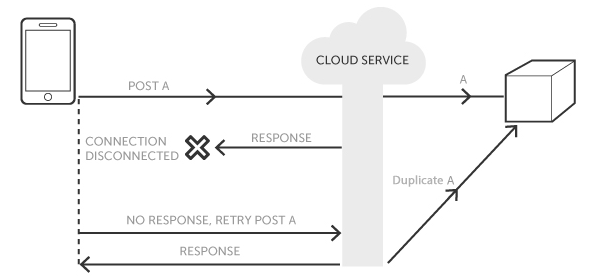

Avoiding repeating POST operations is not always simple. Issues arise for a publisher if, for some reason, it never receives the response to a publish request. This could happen if there was an interruption in the network that caused the response to be lost, or if the publishing process itself crashed before receiving and processing the response. In these situations, the publisher doesn’t know whether or not the publish request has succeeded (typically with a 20x status code response), if it was rejected for some reason, or if it was lost before reaching the server. A typical reaction by a publisher to a publish request that fails without a definite response would be to retry the request. However, it can then happen that both the initial attempt and the retry go on to succeed, in which case the message could have been published more than once.

Services and behavior guarantees

In the above example, the client’s desired outcome – a single message being published – could be achieved if the publish service was advertised as being idempotent (notwithstanding the fact that it is being accessed via POST).

Now imagine that this publishing operation is just one step of a longer transaction pipeline in a service that is composed of multiple individual sub-services. When building that wider distributed service, which has its own functional and behavioral requirements, we have to consider the behavior of each of the constituent services, such as the message bus, in fine detail. In fact, we need to have a well-defined service contract to know what behavior it exhibits, and we need a guarantee that it will continue to do that under all circumstances, even when there are unreliable network connections or other system failures. The behavior of the operations of individual components must all be taken into account when determining whether or not the resulting system upholds its intended behavioral guarantees (such as “at least once”, “at most once”, etc).

It’s also clear that idempotency has specific relevance to the composition of individual services into wider systems. Because it provides a way for certain kinds of failure to be “absorbed” by the system, some failing operations can be retried and, provided they eventually succeed, we know that the results of those failures have not propagated down the pipeline. The implementation of idempotency is an example of one of the recurring challenges when constructing complex and globally distributed systems.

Achieving idempotent publishing for Ably’s pub/sub messaging platform

At Ably, we faced exactly this need for users of our pub/sub platform. We needed to give publishers assurance that publishing via the REST API would be an idempotent process. Before discussing how we did that, it’s worth explaining how the existing message handling and acceptance process works.

When a publisher submits a message to the Ably platform, it will either get a success response, signifying that the message is accepted for onward processing, or an error response, which is a complete rejection – no onward processing will take place for rejected messages. The process Ably uses to determine whether success or failure is the eventual outcome is critical to the service assurances that we make. Aside from validating and accepting a message, we must persist it in a way that assures that all subsequent processing can proceed (in spite of any subsequent internal failures). And those actions, taken together, must be performed atomically. That is, the system must outwardly give the appearance of either all of those steps being completed, or none at all. The critical element of this message acceptance process is to persist and index the message with sufficient redundancy that subsequent processing can always proceed.

We achieved this by persisting messages in multiple datacenters within the region in question. We index them in a way that allows them to be retrieved either by an identifier that indicates their position within a per-channel message sequence, or by another unique message identifier assigned by the system.

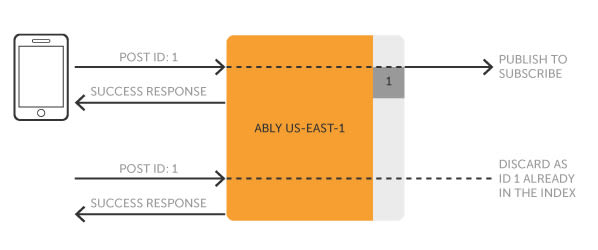

Ensuring Ably’s REST publishes are idempotent – that is, ensuring that the message acceptance step is idempotent – ultimately required little change to the message handling process. Idempotency is achieved simply by allowing the client to supply the unique message identifier instead of assigning it within the Ably service on receipt of the message. Since all messages on a given channel, in a given region, are indexed by this identifier, it is possible to extend the atomic message acceptance step to include an existence check for already-accepted messages with the same identifier. Within a region – and the scope of the existing index – message acceptance can therefore be idempotent.

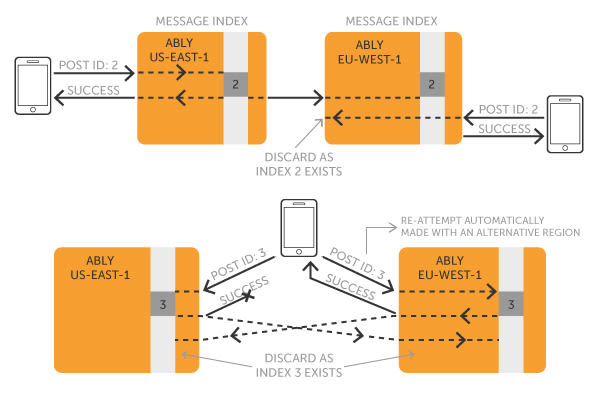

There is always the possibility that a second attempt to publish a message is made against an Ably endpoint in a different region from the first attempt. In fact, in the case of Ably, this will be relatively common – because when a client library experiences a failed API request it will direct subsequent attempts to a fallback endpoint in a different region. If a first attempt in one region (A) happens to succeed but the client nonetheless reattempts in a different region (B), the message is also capable of acceptance there (since the scope of the persistent index is regional).

Now, however, other processes come into play. If the successful publish in A resulted in propagation of the message to region B, then it will belong to region B’s index before the reattempted publish there. In this case, the reattempt will recognize the message as already being present, and so that publish attempt in B will not generate a new message.

A further possibility is that the B publish reattempt happens so quickly that it reaches the B index before the message propagated from A. In this case, the handling of the propagated message will be the operation that recognizes the message as a duplicate, and does not result in further onward processing. The successful acceptance of the B publish of course will also trigger propagation to region A, but the propagated message, on arrival at A, is found to be present in the index and does not trigger further processing there.

As an aside, now that we have made the identifier part of our public publish API, we could have exposed a REST API that makes it explicit that this is an idempotent operation with PUT instead of POST. For example, this is our REST publish:

$ POST rest.ably.io/channels/<<CHANNEL ID>>/messages

{

"id": "<<UNIQUE ID>>",

"data": "<<PAYLOAD>>"

}We could have used PUT as follows:

$ PUT rest.ably.io/channels/<<CHANNEL ID>>/messages/<<MESSAGE ID>>

{

"data": "<<PAYLOAD>>"

}However, we decided against this for two reasons: we still primarily expose the POST API for consistency with other publish operations and our existing SDKs; publishing batches of messages would not be possible with this this URL structure given the messages will have multiple IDs in the case of idempotent publishing.

Implementing idempotency – a user’s guide

When it came to introducing the feature to users of the Ably platform, we took two approaches to ensuring usability.

Implicit idempotency for SDK retries

When our client libraries automatically retry requests that fail, if idempotency is now enabled, an ID is assigned to each message client-side before publishing.

Prior to us adding support for idempotency for REST operations in our Ably client library SDKs (versions 1.0 and lower), the code and resultant HTTP operation are as follows:

client = Ably::Rest::Client.new(key: api_key)

client.channels.get('example').publish([data: 'payload'])$ POST https://rest.ably.io/channels/example/publish

=> {"data":"payload"}

<= Status: 201

<= Body: {"channel"=>"example", "messageId"=>"v8THreaglB:0"}Note how the Ably service itself assigns a unique identifier to the message in the response. Now when idempotency is enabled in the client library SDK explicitly, the client library itself assigns a message ID before the message is published ensuring any automatic retries by the client library will be idempotent.

client = Ably::Rest::Client.new(key: api_key, idempotent_rest_publishing: true)

client.channels.get('example').publish([data: 'payload'])$ POST https://rest.ably.io/channels/example/publish

=> {"data":"payload","id":"FBE7nsDHP/oe:0"}

<= Status: 201

<= Body: {"channel"=>"example", "messageId"=>"FBE7nsDHP/oe:0"}Explicit client-supplied IDs for idempotency

Whilst client library-assigned message IDs provide idempotency for automatic retries by the client library, client-supplied IDs can now be provided trivially, thus allowing the publisher to freely publish the same message from one or more workers in their system, without fear of duplication.

client = Ably::Rest::Client.new(key: api_key)

client.channels.get('example').publish([data: 'payload', id: 'unique123'])$ POST https://rest.ably.io/channels/example/publish

=> {"data":"payload","id":"unique123"}

<= Status: 201

<= Body: {"channel"=>"example", "messageId"=>"unique123"}If you want to find out more, view the Ably REST documentation on idempotency.

Idempotency and Ably

Ably is an enterprise-ready pub/sub messaging platform. We make it easy to efficiently design, quickly ship, and seamlessly scale critical realtime functionality delivered directly to end-users. Everyday we deliver billions of realtime messages to millions of users for thousands of companies.

We power the apps people, organizations, and enterprises depend on everyday like Lightspeed System’s realtime device management platform for over seven million school-owned devices, Vitac’s live captioning for 100s of millions of multilingual viewers for events like the Olympic Games, and Split’s realtime feature flagging for one trillion feature flags per month.

We’re the only pub/sub platform with a suite of baked-in services to build complete realtime functionality: presence shows a driver’s live GPS location on a home-delivery app, history instantly loads the most recent score when opening a sports app, stream resume automatically handles reconnection when swapping networks, and our integrations extend Ably into third-party clouds and systems like AWS Kinesis and RabbitMQ. With 25+ SDKs we target every major platform across web, mobile, and IoT.

Our platform is mathematically modelled around Four Pillars of Dependability so we’re able to ensure messages don’t get lost while still being delivered at low latency over a secure, reliable, and highly available global edge network.

Developers from startups to industrial giants choose to build on Ably because they simplify engineering, minimize DevOps overhead, and increase development velocity.

Idempotency is one of several features whose absence is felt more acutely when beginning to stream at scale, or if it becomes part of an organization’s "mission-critical" operations – such as in-play betting or payment apps. At Ably, we provide baked-in idempotent publishing, which helps ensure that published messages are processed only once, even if a client or connectivity failure causes a publish to be reattempted.

References and further reading

Ably Engineering blog, which covers a wide spectrum of engineering challenges related to building a globally-distributed serverless realtime infrastructure at scale

Definition of idempotency in the HTTP specification (RFC 7231)

Recommended Articles

What is Pub/Sub? The Publish/Subscribe model explained

Learn everything you need to know about Pub/Sub, a design pattern that’s used to implement event-driven architectures and realtime messaging systems.

What is a realtime API?

What realtime APIs are, the different types of realtime API, how they operate, and when to use them in your applications.

Pub/Sub pattern architecture

Learn about the key components involved in any Pub/Sub system, understand the characteristics of Pub/Sub architecture, and explore its benefits.